As the world begins to find its way back to normalcy, it saddens me that the COVID-19 pandemic is still having devastating effects on the Black community. But as a Black woman who is a victim of healthcare discrimination and mistreatment myself, I have to admit I am not surprised, either.

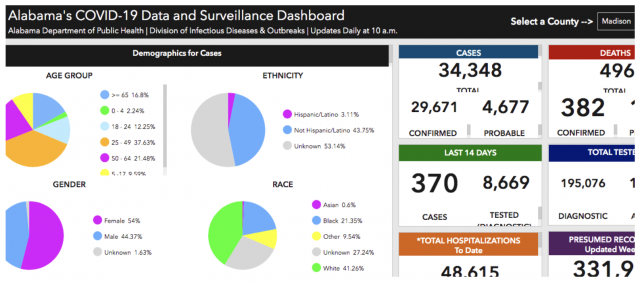

According to the Alabama COVID-19 Data and Surveillance Dashboard, about 43% percent of COVID-19 cases in Madison County have been Black people. This may not seem like an overwhelming rate, but we also know that black people only make up 24% percent of the population in that county.

Seeing these health inequities made me wonder about how differently this pandemic is impacting Black and brown people, and how the hidden factor of racism influences our health outcomes when we go to a hospital for a serious disease that requires medical treatment.

Then, in the summer of 2020, cell phone video footage surfaced on YouTube showing a biracial couple being mistreated in the 24 hours after the birth of their child–at the same hospital where I had given birth twice and had more than one horrible experience with staff members.

Witnessing that family’s mistreatment on video made me dig deeper into my own birth stories and reflect back on how I was mistreated as a Black woman in the hospital during two of the most important events of my life.

IT’S STILL HAPPENING: THE WASHINGTON FAMILY IN 2020

The recording posted by the Washington family shows hospital workers directing attitudes of annoyance at the Black father just for asking questions about the care of his child and wife. Though the father speaks perfectly calmly throughout the conversations, a staff member states they feel “threatened” and the hospital then changes the requirements for the couple to be able to take their child home.

The staff repeatedly says they must follow guidelines and policies, but they have no reasonable explanation healthwise as to why the child cannot go home. Between the bewildered, frustrated parents and the irritated staff, this all culminates in a staff member actually calling the police, and a confrontation between a hostile police officer and the sobbing mother who has just given birth, as her husband tries to advocate for her with his mother on speaker phone giving them support. Just one of the shocking moments in this exchange is the officer repeatedly asking the birthing mother for identification as she lies in her hospital bed cradling her new baby.

I encourage you to watch the entire video to witness their full story.

A 2019 study found that experiences of mistreatment during pregnancy and childbirth in the U.S. were consistently higher for Black parents. Having a Black partner increased reported mistreatment regardless of the birthing person’s race. The researchers reported “For some indicators of mistreatment (e.g., Health care providers ignored you, refused your request for help, or failed to respond to requests for help in a reasonable amount of time) White women with a Black partner were twice as likely to report mistreatment when compared to White women with a White partner.”

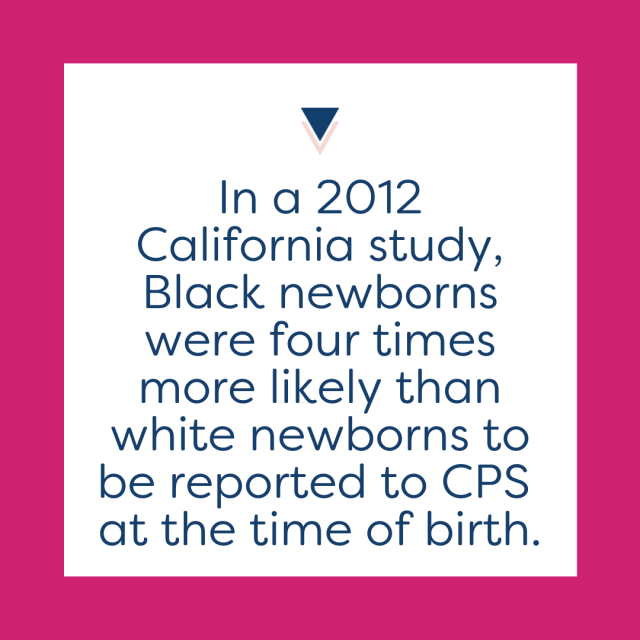

There are also documented racial disparities in Child Protective Services (CPS) reporting. In a 2012 study from California, Black newborns were four times more likely than white newborns to be reported to CPS at the time of birth. This was despite similar rates of alcohol and illicit drug use identified in Black and white pregnant people in prenatal care. So, failing to comply with medical recommendations carries more risk to Black parents. White parents can raise their voices and question authority figures with more liberty—without as great a fear of intervention by police or social services.

After watching the video and having a conversation with the family, I was disappointed to realize that it seemed like the hospital had not followed through on my own petitions to them to educate themselves about their misconduct. After having two babies born at Huntsville Hospital for Women and Children, I pleaded with them on multiple occasions to implement more training and education, and I had hoped that real changes were made to better the care of patients.

In addition to giving birth there, I have also been hired by patients as a doula to attend births, and been employed at the parent company for the hospital–each time resulting in a negative experience. It seems to be more than a few rare incidents but a systemic pattern they choose not to change.

The Washington family did have a meeting with the hospital after the incident, but as of the publication date of this article, nothing had been achieved. Mr. Washington said, “They told us they would be taking steps forward to improve and that we would be a part of the process. They never reached out and ignored several phone calls.”

THE EVIDENCE OF MY OWN EXPERIENCE WITH BABY #2

The World Health Organization states that “addressing inequalities that affect health outcomes, especially sexual and reproductive health and rights and gender, is fundamental to ensuring all women have access to respectful and high-quality maternity care.” But respectful and high-quality are definitely not the words I would use to describe my births.

In 2015, I gave birth to my second child at Madison Hospital in Alabama. Both doctors and nursing staff treated me so negatively, I doubted my strength and ability to give birth. My pregnancy and birth were met with discrimination and racist remarks. I heard comments like “Do you have the same father for your kids?” and “Because of your weight you are not a good candidate for VBAC (vaginal birth after Cesarean).” I was never shown data, documents, or reports that supported the statements they made. During birthing transition–the hardest part of labor–I was told to “shush” and “calm down.”

Janice A. Sabin, Ph.D., MSW is one of the first researchers to apply the science of implicit bias to the health care system. In a January 2020 article, she discussed a 2016 study that found that “40 percent of first and second-year medical students endorsed the belief that black people’s skin is thicker than white people’s.”

For more on the story, visit my interview with Birth Monopoly founder Cristen Pascucci.

In the end, my doctor didn’t even want to enter my room. From my doorway, all he said was “I guess you were right,” about me successfully having a VBAC.

ALONE IN A BUILDING FULL OF PEOPLE WITH BABY #3

Two years later, I was pregnant with my third child. After how I was mistreated during my last birth, I delayed seeking obstetric care until well into the second trimester. I chose a new office with a new set of doctors after a referral from a close white friend. My friend had nothing but rave reviews and I was excited to have a new birthing experience I could be excited about.

When I arrived, I was treated fairly well. But when I spoke very clearly to my doctor about the unsupportive care I received with my previous birth, she responded, “That was probably just a bad day.” Now, I understand not wanting to talk negatively about a colleague, but having my traumatic experience minimized by my care provider was not what I needed as a pregnant patient.

After that, my anxiety built and birth became something I dreaded. I wanted it over with as soon as possible. I couldn’t enjoy the precious moments of growing a child.

Ten weeks after that appointment, my water broke early at the estimated 35-week mark while my husband was away with my daughter as she had surgery. When I arrived at Huntsville Hospital alone, I was made to sit in a waiting room as amniotic fluid dripped down my leg. Once I was in triage, a nurse performed a vaginal exam on me, and when I asked her to stop, she proceeded to continue the exam while I backed further away from her in the hospital bed in pain. She just kept going. Afterwards, she said, “If you[d] relaxed it would not have hurt.” I felt violated.

With my husband and daughter away, I had no one. A building full of people, and I was alone. In that moment, I decided to call another family member, who was two hours away on business, to make the trip and be my support person. In the back of my mind, I knew I needed someone there just in case something happened to me. Or in case something else was done to me.

The moment I was transferred to my room, I let my nurse know immediately about how I had been assaulted in triage. I do not believe she reported it to anyone.

But from there, after such a bad start, my son had a beautiful entrance into the world. I was honestly shocked. My doctor was extremely caring, the nurses were amazing, and I was on cloud nine after bringing my child earthside with no medication in three easy pushes.

WHEN CAN I FEED MY BABY???

That bliss quickly ended when I was told my son needed to be transferred to the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit (NICU) to “get warmed up” and help him regulate his temperature. I waited for hours with no status updates–I had not yet been able to breastfeed him, a moment I look forward to with each birth.

When I was eventually allowed to visit him, my son had machines and wires everywhere, and we were told we could not hold or even touch him. I asked again, “When can I feed him?” I was told he had to be cleared by the neonatologist… who didn’t come in until the next morning.

Now I was frantic, but I got to work. I started pumping right away and kept going through the night so I would be ready for my baby. I called the NICU several times during the night to check on him and discuss his first feed with his nurse.

Finally, after a long and exhausting night, I called at the time instructed by his nurse to see if I could come to the NICU. The news broke my heart. She told me that she had actually already fed him–two hours earlier than she told me she would.

I was distraught and hurt that I did not get to give my son his first meal earthside. When I contacted the supervisors, I was told to “calm down if I wanted my concerns to be heard” and the nurse “didn’t realize it was such a big deal.”

Why would feeding my child for the first time not be a big deal to me? Why disregard my request to exclusively breastfeed?

I spent the remainder of his stay on eggshells. I could not wait to take my son home and never return. It is easy for others to say “but your child is home and healthy,” but those traumatizing experiences imprint on memories that are supposed to be joyous.

I sent a grievance email once my son was home and my thoughts were organized. I received an email from their communications coordinator with her deepest apologies. She offered an opportunity to join a community committee that would improve the treatment in the NICU. I was excited about her proposition.

That committee was never created, and I never got a call back.

NO REAL ACCOUNTABILITY

I figured the best way to contribute to health equity was to participate in the care of patients, so I decided to put those experiences behind me and get involved on the inside. I accepted an opportunity to work in the hospital as a lactation counselor and educator. As a certified lactation counselor, I love helping families reach their breastfeeding and parenting goals.

Corporate training was a week long, and it was difficult to hear the hospital talk about their high standards for patient care–knowing my sons and I didn’t receive high-quality care there. During the training, we had to watch a video that spoke about empathy, which you can watch here. It seemed like the only lesson on interacting with patients.

I started training at Madison Hospital for more in-depth training for my title role, learning to dress wombs, use restraints, and calculate urine measurements. When it was time to learn telemetry, the trainer shared a color coordination tactic to help us remember. She told us to remember the color white as “white is right.” She said this in a room with four people of color. She said it again: “see it rhymes, white is right.” I stated that is not something they should be teaching, but she did not understand my discomfort with the statement. I immediately let my supervisor know and was met with, “Oh that’s just how we have all learned it,” and, “She did not mean it like that, she is really nice.” I repeated my discomfort with the statement and was told they would make sure she did not use it again.

The Alberta Civil Liberties Research Center has a complete list of the many forms of racism. They share the definition of systemic racism as “policies and practices entrenched in established institutions, which result in the exclusion or promotion of designated groups. It differs from overt discrimination in that no individual intent is necessary.” Indeed, this trainer has been teaching this to multiple employees who maybe still using the terms in the workplace, and when I reported it, I was met first with dismissal and then with no meaningful followup action taken. No internal memo was ever sent out, and no diversity or sensitivity education was ever implemented to my knowledge.

How will Black patients receive respectful care from a system that can’t see why this phrase is problematic and doesn’t really address it when a Black person alerts them that it is?

But trainers are not the only ones contributing to systemic racism. A practicing doctor at Madison Hospital posted on his personal public Facebook page that “lay midwives are the dumbest thing since pet rocks.” Now, there is historical importance to Black “granny” midwives (now called “Grand Midwives”) in the U.S. south, some who had the responsibility of not only caring for slave owners but also enslaved Blacks. They were not medically trained but passed down the history of care through generations. After a coordinated campaign by white men in the early 1900s to discredit their skills, cleanliness, and safety, granny midwives became virtually non-existent as families were funnelled into hospital care.

You see, the racism goes deep and has such a long history. Part of the reason we are mistreated in hospitals is that we don’t have options for care in our communities other than hospitals! Our own Black midwives were taken from us. So why would a healthcare system change when it knows patients have nowhere else to go anyway?

Of course, it is difficult to prove mistreatment, and even when it has happened, there are no real consequences for the people who have committed the offense. Reports and grievances just are not taken seriously. There is no way to follow up with a hospital about changes without getting back, “We decided to handle it internally”–even though, as a Black woman, I am 3 to 5 times more likely to die giving birth compared to my white counterparts according to the CDC. These issues are real and urgent and not fixing them literally costs lives. The stakes are highest for people like me.

I wanted to end this blog with some helpful tips to make you feel more confident about reporting mistreatment:

- Take a picture of your room board. This has all the names of people assigned to your room.

- Keep a notepad on your phone of incidents when they are fresh in your mind.

- Ask to speak to the head nurse or supervisor.

- Report everyone who mistreated you, from the doctors to the nurses. REPORT!

- You are allowed to ask for a new nurse and fire your doctor at any time.

- Send emails and keep copies of them.

- If they are requesting a meeting, write a letter on paper to read out loud–this way you have all your thoughts in one place.

- Quote their policies!! If you are told something is policy, ask to see it in writing.

- Trust your gut.

- This is truly a global issue. Multiple families document their mistreatment by way of the “Obstetric Violence Map” on Birth Monopoly’s website, from medication not consented to, to not being given all the information or options to make their healthcare decisions. Add your story to the map.

Author: Sabrina Butler, CLC | What started out as a journey in parenting propelled Sabrina into her true calling of community advocacy and empowerment. Self-describing herself as “the nerd who became cool after having kids” has spent the past 6 years building community relationships, assisting companies and programs in anti-racism initiatives, and introducing families all over to alternative ways to parenting, motherhood, and service. She continues to offer lactation services in surrounding areas of Tucson, Arizona while pursuing her doctorate degree in Public Health at the University of Arizona. Follow Sabrina on Twitter or visit www.rsbstratagies.com to schedule a virtual or in-person appointment.

Author: Sabrina Butler, CLC | What started out as a journey in parenting propelled Sabrina into her true calling of community advocacy and empowerment. Self-describing herself as “the nerd who became cool after having kids” has spent the past 6 years building community relationships, assisting companies and programs in anti-racism initiatives, and introducing families all over to alternative ways to parenting, motherhood, and service. She continues to offer lactation services in surrounding areas of Tucson, Arizona while pursuing her doctorate degree in Public Health at the University of Arizona. Follow Sabrina on Twitter or visit www.rsbstratagies.com to schedule a virtual or in-person appointment.

I believe that the vast majority of medical “professionals” don’t love their work and just go through the motions of earning a salary. I watched the video and I couldn’t help thinking how unhealthful the medical personnel look. The obese male nurse was the icing on the cake. How could people like these know anything about health? They look in dire need of healthcare themselves. I, personally, hired a midwife who is hysterectomized. No wonder she almost killed me with medically unnecessary medical interventions for more profit. Lesson learned, do not trust unhealthful people, they live severely compromised lives and cannot possibly rise to the level of true care for someone else.