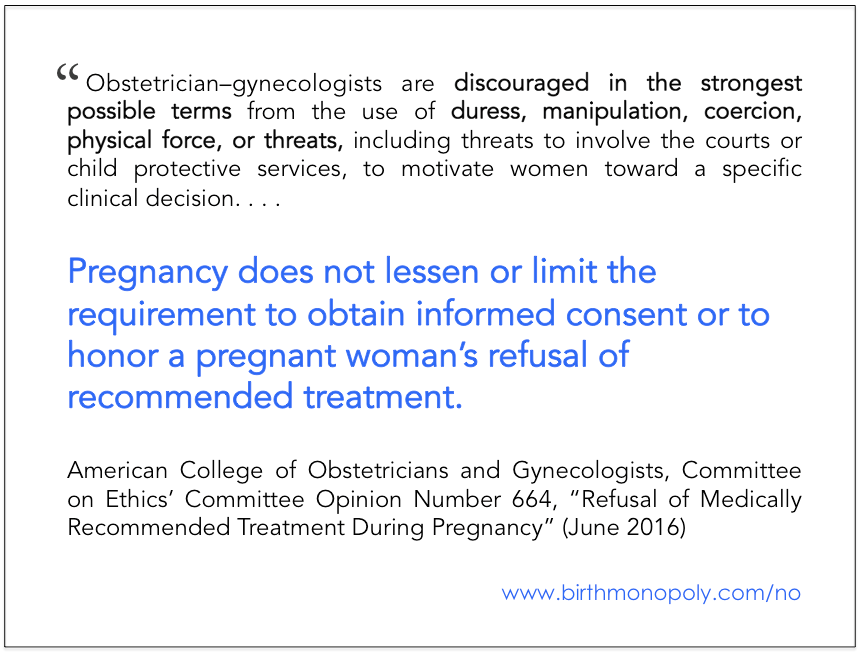

A new ethics opinion from the U.S. obstetrician’s organization makes it clear that a woman’s right to say “no” in her medical treatment is paramount, and takes precedence over concerns about fetal well-being. The committee urges doctors to respect “fundamental values, such as the pregnant woman’s autonomy and control over her body,” and discourages them “in the strongest possible terms” from the use of coercion and court-ordered threats or interventions.

This is critical at a time when doctors, hospitals, and judges regularly co-opt women’s decision-making in pregnancy and birth, as documented by multiple court cases around the country (Turbin vs. Abbazzi, et al. in California, Dray vs. Staten Island Hospital, et al. in New York, Switzer vs. Rezvina, et al. in New Jersey, Malatesta vs. Brookwood Medical Center, et al. in Alabama [Ms. Malatesta’s own story is here]–all of which are in progress now, except for Switzer, which was resolved in late 2015) and by widespread reports from women themselves, such as were compiled in firsthand accounts here (see Exhibit B in the embedded PDF about halfway down the page), here, here, and here. In September 2015, consumer advocates wrote a letter to ACOG asking them to address the issue of disrespect and abuse in maternity care.

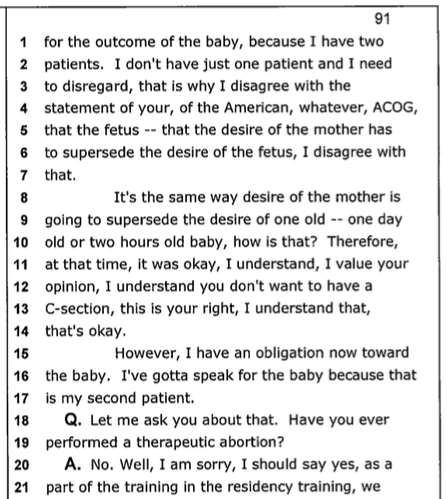

From deposition of Dr. Natalia Rezvina, Switzer vs. Rezvina et al.

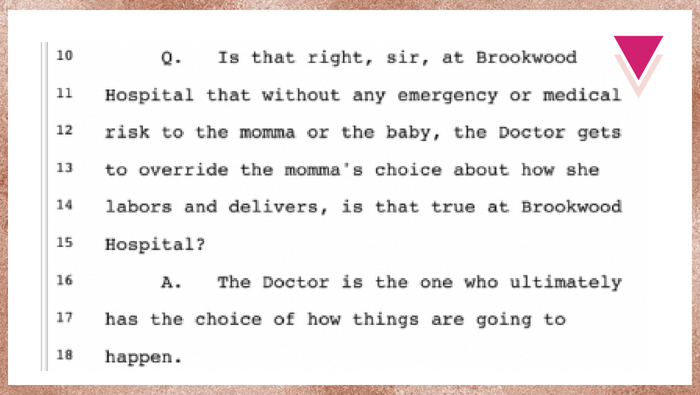

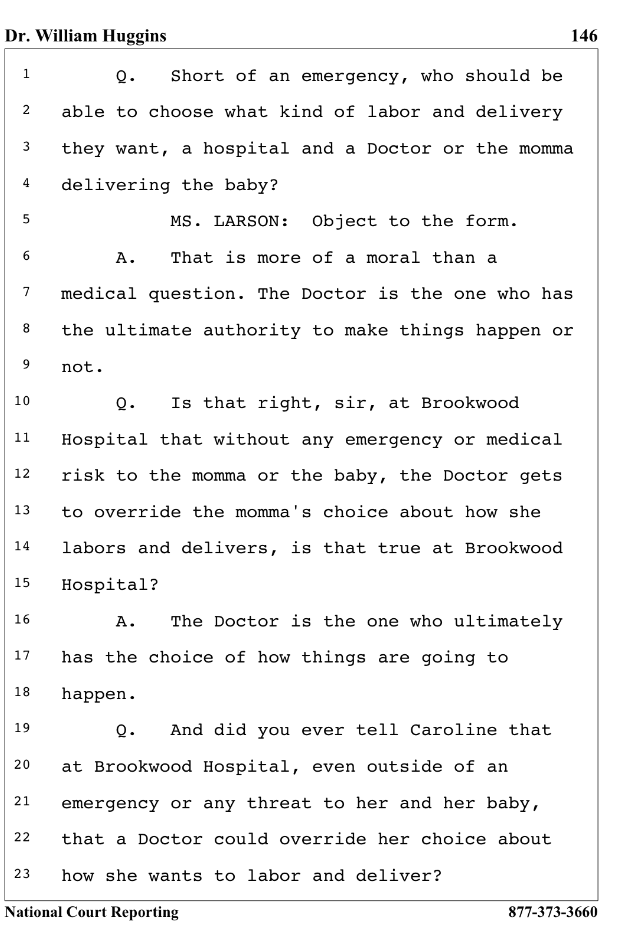

Indeed, the safety of the baby is very often cited when women are harmed with forced interventions, including in the court cases listed above. In Ms. Switzer’s case, the doctor said in deposition that she had “two patients” and asserted that she (the doctor) must speak for the “desire of the fetus” (see page 91 in file titled “Natalia Rezvina’s Deposition: ‘I do not agree with your American, whatever, ACOG,’” here). Ms. Switzer and her lawyers maintained that there was never an emergency and her written consent for Cesarean was given under duress and threat of involvement by “legal people” and social services. Lawyers for Staten Island Hospital in the Dray case went so far to claim that women do not have due process rights in childbirth in the case of an “emergency”; however, that defense team called it an “emergency” that Ms. Dray was having the vaginal birth after Cesarean that she and her doctor had planned all along. In Ms. Malatesta’s case, her attending doctor (not named in the lawsuit, and not present during the alleged physical battery she experienced) stated that he believed the physician, not the mother, had the “ultimate choice” in childbirth–even when there was no emergency.

From deposition of Dr. William Huggins, Malatesta vs. Brookwood, et al.

Below are some highlights from the Committee on Ethics’ Committee Opinion Number 664, “Refusal of Medically Recommended Treatment During Pregnancy” (June 2016), which replaces Committee Opinion Number 321, “Maternal Decision Making, Ethics and the Law” from 2005. (See Birth Monopoly’s #ACOGethics for other ethics committee guidelines that apply to pregnant and birthing people.) Please note that, although committee opinions such as these may be used as evidence in court cases, committee opinions do not carry the weight of law.

In the opening section, “Complexities of Refusal of Medically Recommended Treatment,” the committee talks about the relationship between pregnant women and fetuses, stating that their interests typically converge, and pregnant women usually decide for the “best interest of their fetuses.” They also note that any treatment of the fetus occurs “through the body” of the woman (emphasis added). The committee notes that conceptualizing the woman and fetus as separate entities can cause the interests and rights of the woman to become secondary, and may even lead to the woman “being seen as a ‘fetal container’ rather than an autonomous agent.”

The committee then addresses “Directive Counseling vs. Coercion,” instructing OBs to participate in the former only–calling coercion (the use of force or threats to compel someone to do something) “ethically impermissible but also medically inadvisable” and “never acceptable” for obstetrician/gynecologists. It also acknowledges limitations on the certainty of medical outcomes and knowledge.

The committee discusses “Arguments Against Court-Ordered Interventions” as abuses of power and encroachments upon the pregnant woman’s rights, autonomy, and bodily integrity that often disproportionately affect women of color or of low socioeconomic status. It notes 1987 and 2013 papers showing that most cases where court orders were sought involved women in these two groups; the 1987 paper also showed the medical judgment had been in error in almost one-third of the cases.

So what does a doctor do when a pregnant woman refuses his or recommendation for a medical treatment? The committee advises them to carefully note the woman’s refusal in her medical records, including documenting the informed consent discussion (risks, potential benefits, alternatives) and the refusal of consent and reasons for the refusal. Under the heading “Process for Addressing Refusal of Medically Recommended Treatment During Pregnancy,” the committee lists a number of steps to guide physicians through understanding and engaging with their patients throughout the informed consent process. Box 1 outlines the “RESPECT Communication Model,” one tool that can help physicians engage in meaningful communication with their patients, even when time is short.

Last, the committee acknowledges the need for “Supporting the Patient and the Health Care Team When Adverse Outcomes Occur,” as all parties may experience distress, regret, or grief at that time. It stresses “honest communication and compassionate support” for all involved and recommends that counseling and debriefing resources are made available to medical professionals. In communicating with the patient, physicians are advised that her grief comes first, as “judgmental or punishing behaviors . . . can be harmful.”

This opinion is an excellent resource, but consumers, advocates, and physician champions must continue to address the disconnect between the ideals it expresses and actual maternity care practice. What can we do to further awareness and education among medical professionals, as well as providing protections for women who do experience coercion and forceful interventions?

A former communications strategist at a top public affairs firm in Baltimore, Maryland, Cristen Pascucci is the founder of Birth Monopoly, co-creator of the Exposing the Silence Project, and, since 2012, vice president of the national consumer advocacy organization Improving Birth. In that time, she has run an emergency hotline for women facing threats to their legal rights in childbirth, created a viral consumer campaign to “Break the Silence” on trauma and abuse in childbirth, and helped put the maternity care crisis in national media. Today, she is a leading voice for women giving birth, speaking around the country and consulting privately for consumers and professionals on issues related to birth rights and options.

A former communications strategist at a top public affairs firm in Baltimore, Maryland, Cristen Pascucci is the founder of Birth Monopoly, co-creator of the Exposing the Silence Project, and, since 2012, vice president of the national consumer advocacy organization Improving Birth. In that time, she has run an emergency hotline for women facing threats to their legal rights in childbirth, created a viral consumer campaign to “Break the Silence” on trauma and abuse in childbirth, and helped put the maternity care crisis in national media. Today, she is a leading voice for women giving birth, speaking around the country and consulting privately for consumers and professionals on issues related to birth rights and options.

Consult with Cristen | Resources + more Articles

Free handouts + monthly-ish updates from Birth Monopoly: click here