Foreword

I wrote this article to publish in 2017 and never got it out. Now putting it out in 2022, I thought I should update the 2013-2016 examples I used throughout. So, I went to our map of obstetric violence stories, starting with the very last entry we have there –from eight days ago (December 21, 2022).

A doula described a doctor about to do a cervical exam on her patient without consent, then pressuring the patient to have the exam, then repeatedly touching the patient without consent during the final pushing phase, until the patient yelled at the doctor to stop touching her. I thought, what is the point of updating these examples when they look the same today?

The other reality is that it’s emotionally difficult and heavy for me to dig through story after story of violence against birthing people. It takes a lot of energy, and it takes me to a place of sadness and hopelessness. In 2022, almost 2023, I need that energy to work on solving the problem and in forward movement.

So, I chose to add just that one example in from 2022, do some light editing, and give you the rest of the article as-is. It might read a little funny because of its age, but I also think it’s interesting to see this pre-Trump, pre-COVID, pre-Roe-being-overturned snapshot in time.

Birth in Rape Culture

“He starts rolling my blanket up and I’m like, no, don’t, holding the blanket down. . . . I was like, please… So he moved my legs apart and he’s like it’s not going to hurt. I said no, no, and put my legs together. He actively pushed my leg to the side and stuck the thing in me. That was the most traumatizing thing, I had just said no and he did it anyway. He said, stay still! I was really upset and after that . . . I remember crying and falling asleep.” – S., New Jersey, about a doctor at her child’s birth

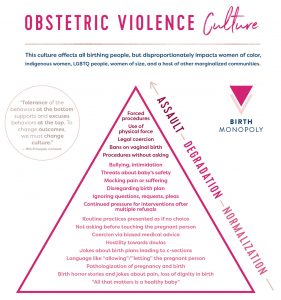

Rape culture is about the normalization and tolerance of sexual violence against women, and that culture is alive and well in maternity care, where the appropriation and control of the pregnant body is ubiquitous. We call this obstetric violence.

Exacerbated by the power imbalance that naturally exists in healthcare settings, women and birthing people are told from early pregnancy through birth what they are “allowed” and “not allowed” to do, from how long they are allowed to be pregnant to eating and drinking in labor to how long they may push and the actual position in which they are compelled or instructed or even forced to do so. In Labor and Delivery, anything can happen to a woman’s body, and she will be told, implicitly and explicitly, to be grateful.

Choice and Consent

Take the case of Caroline Malatesta, who filed a lawsuit after the 2012 birth of her fourth child at a Birmingham, Alabama, hospital that used words like “autonomy,” “options,” and “choice” in a massive advertising campaign aimed at mothers like her who were looking for a woman-centered model.

She and her husband described how a nurse grabbed Caroline’s wrist and yanked it out from under her to pull her onto her back from hands and knees; at the same time, another nurse forcibly held in the baby’s head to prevent his birth until the doctor arrived. A straightforward, unmedicated birth became a wrestling match that left a woman with permanent, incapacitating internal injuries.

The freedom of movement and choice the hospital and her doctor had promised Caroline were just marketing tactics. Contrary to everything she had been told, Caroline’s nurses were actually under standing orders for all women to be on bedrest–apparently, by any means necessary. Meanwhile, in court, the hospital simultaneously stood by their marketing claim that they support women having the choice for position while also arguing that choice is “not determined by the mother’s preference” alone. It was “unreasonable,” they said, “for Ms. Malatesta to have read [our marketing claims] and said . . . she has the right to choose to go to hands and knees with no other consideration.” Caroline’s own doctor said that even “without medical emergency or medical risk to the momma or the baby, the doctor gets to override the momma’s [sic] choice about how she labors and delivers.”

In a landmark verdict, the court found for the Malatestas–an unusual outcome in a system where violations of patients in the obstetric setting are routinely ignored and dismissed. The $16 million award was intended to punish the hospital for lying about its services as well as compensate the couple. Caroline can never again have sex and will need round-the-clock medical management for the rest of her life to manage her nerve pain.

Another woman in New York state, who was not able to bring a lawsuit, describes here the unmedicated 2013 birth of her healthy baby, which her medical records characterized as “uncomplicated” [link]:

The nurse screamed “GET ON YOUR BACK NOW” and two nurses grabbed my arms and legs . . . flipping me onto my back. They wrenched my legs open, forcing my knees toward my ears . . . The doctor put her hand in my vagina which caused a great deal of pain. I was filled with terror as the nurses held me down and I pushed my baby out. . . . The noise, pain . . . and unknown people’s hands touching my vagina and my thighs terrified me and I still have PTSD symptoms.

What happened next confirmed to this woman that the hospital, in fact, did see her body as theirs to manipulate during labor and birth. When she contacted them to ask why she’d been treated so violently, “they firmly stated that all women deliver on their backs in that hospital, legs immobilized in stirrups or held by nurses, and if a woman is not on her back when the doctor wants her to be, she will be forcibly moved into that position.” The woman followed up with the Joint Commission, the body that accredits the majority of U.S. hospitals, who determined that the hospital’s “response is acceptable at this time” and did not reply to the woman’s subsequent questions.

In 2014, hundreds of stories were shared through a grassroots social media campaign called #BreaktheSilence I helped create as vice president of a national maternity care advocacy group. One was this, from a doula:

One of my clients had narcotic pain relief and was napping. The on-call OB came in, did a cervical exam, and ruptured her membranes when she was asleep. When I realized what he was doing, I asked if he was going to wake her first. He said, ‘I don’t need her permission. I would do it anyway.’

In 2016, a Kentucky woman reported that, during a vaginal exam in early labor, her doctor decided to do an elective procedure without her consent. This procedure, done while the doctor’s hands were still inside her after checking her dilation, was meant to “speed up labor.” To no avail, the woman tried to stop it, screaming in pain, pushing away, and begging the doctor to stop. After an investigation, the hospital justified the doctor’s actions in that the woman hadn’t said, “No,” to the surprise procedure before it happened, but only during it. In addition, they alleged she had implied consent by not objecting to the idea of that procedure as an option weeks before.

A woman in Utah complained to her hospital about a doctor performing a non-emergency vaginal procedure on her without consent during her 2016 birth. She says the response from the head of Labor & Delivery was that the “blanket” consent form she signed upon admission gave them all the permission they needed. A subsequent internal hospital review confirmed that view, finding her care to have been “appropriate.” This is crucial: if the hospital maintains that signing a consent form means your basic consent rights no longer apply, and all pregnant patients must sign such forms in order to be admitted, the hospital has formalized a policy of violating the consent rights of their pregnant patients.

This idea flouts human rights and U.S. constitutional principles, as well as guidelines from the obstetricians’ professional organization. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) has roundly and repeatedly rejected attempts to lessen or remove basic rights from pregnant patients, such as in a 2016 ethics statement when they stated: “Pregnancy is not an exception to the principle that a decisionally capable patient has the right to refuse treatment, even treatment needed to maintain life.” [link]

Vilification of Victims

I have observed that anyone who speaks up about their mistreatment in maternity care will find they face all the barriers of a pre-feminist society. They will find, as with so many rape victims in previous eras, the onus is on them to prove their story, their motives, and their damages, while the accused is innocent until proven guilty. They will be told “there must have been a reason” their care provider did what they did. Surely, it must have been “for their own good” or the baby’s good that their rights were violated.

A woman named Katie in Arizona lost both her twins immediately after their unexpected premature births. What compounded that tragedy, however, was what happened as she and her family sat crying and holding the babies’ bodies in the delivery room. A male resident entered the room and, without asking, inserted a hand up her vagina to her uterus to start “cleaning her out” (his words). In pain, she begged him to stop but he did not, dismissing her cries by saying she shouldn’t be able to feel it even as she said she could. When she finally opened up about this experience to a coworker:

She told me it’s selfish people like me who can’t get over things is why there aren’t any good doctors anymore… because we ‘sue for everything.’ I did not sue and wasn’t planning on it. It wasn’t about that, it was about my consent, my worth as a person, and how I was treated in those awful moments right after I had to watch my babies die.

Another Alabama woman, E., says her doctor actually laughed at her screams of pain as E. followed instructions to hold back from pushing while the doctor prepared herself for delivery. When E.’s distress turned out to be founded in a true emergency, the doctor panicked and mismanaged the crisis, resulting in an injured baby. Her son required several surgeries and daily physical therapy in his first years–care E. vigilantly oversaw as she dealt with her own PTSD from his birth.

I was called “absolutely disgusting” by someone I considered a friend because I expressed ambivalence concerning my feelings of guilt surrounding the birth. I expressed that I felt like the outcome was all my fault but at the same time… I trusted my care provider completely. Apparently I deserved everything that happened because I trusted the wrong person and yes, everything was, in fact, all my fault. Then there’s the gaggle of people who dismiss my entire experience because I must have misunderstood what was going on because emergencies are scary and confusing and a board certified OB would never do anything that wasn’t in my best interest. And I really should just stop talking about all this because it makes me look like a bitter, angry woman.

E.’s last comment frames another typical response: that to call out abuse in birth, one must be a “doctor hater” or “anti-hospital.” But each of these examples is of someone who willingly chose hospital care administered by medical professionals. They felt hospitals would provide the safest setting for them and their babies and they assumed that they would receive competent, humane care from skilled providers. Instead, they discover they’ve entered a world where their consent rights are the trade-off they make for care. It’s no different than the reality we encounter as women when we date men and end up assaulted or work hard to earn jobs in male-dominated fields only to be harrassed. These are the experiences women have existing in the world, and they should reflect on the abuser rather than the victim.

In 2015, I interviewed dozens of women last year about their traumatic births [link]. It was striking how many of them described being “gaslighted” when they tried to talk about what had happened afterwards. They described being dismissed, ignored, talked over, and even personally attacked when they expressed grief about how they’d been treated during childbirth. That lack of validation is a second trauma on top of the first.

The ways victims of obstetric violence are silenced are strikingly similar to what victims of sexual violence report. We need to be aware of the cognitive dissonance when we treat obstetric violence victims as less trustworthy, less sane, or more deserving of violence than any other group of survivors.

Maternity Care as Sexual Violation

“I want to say to my doctor, ‘I think about you every time I have sex with my husband. Was that your intention?’ See, he didn’t ask before he put his fingers in my vagina just as I was trying to push out my baby. Then he refused to remove them when I asked, then pleaded with him, ‘Take your fingers out of my vagina!’ Actually, he said to me, ‘You don’t need to talk to me like that.’” – J., Delaware

Medical professionalsl administering what they consider routine care can in fact be sexually traumatizing their patients in pregnancy and birth when they act on their sexual organs without explicit consent. The potential for trauma is even greater for the significant number of women who have already been abused or sexually victimized in their lives. ACOG advises that for this group of people, “past feelings of powerlessness, violation, and fear” can re-emerge in a setting where they are “in the lithotomy [back-lying] position and being examined by relative strangers” [link]

At the 2013 birth of her first child, Kimberly Turbin in California let her care providers know she was a two-time rape survivor and asked them to be extra patient and communicative with her. Instead, her doctor made fun of her and took a pair of scissors to her perineum against her will. She said “No! Don’t cut me!” and he did, twelve times, like he was slicing a pizza. The entire interaction was caught on video. Kimberly’s mother, off-camera, can be heard encouraging the doctor to ignore her daughter and admonishing Kimberly to listen and obey.

The PTSD Kimberly had already been fighting from her rapes re-emerged following the birth. She said afterwards, “I dealt with those assaults by going to therapy. Birth, I thought by letting everyone know about those assaults, they’d respect me considering they were professionals. But [birth] was the worst assault I’ve ever faced because it was the most violent and took 6 months to heal from the worst of it and three years to even get a diagnosis!” No one in her immediate circles supported her in her trauma. For months after the birth, she repeatedly sought medical care for additional physical injuries and was dismissed out of hand. One healthcare worker told her that if she couldn’t engage in vaginal sex any more, she could satisfy her man with anal sex. And above all, everyone told her, she had “a healthy baby,” and that was really what mattered.

Not too long ago in the United States, domestic violence, marital rape, and sexual harassment were considered fairly normal life experiences for women. The law allowed little or no protections, and society, for the most part, shrugged and accepted these unfortunate realities. The legal protections we have against them now are relatively new and still inadequate, but they are far more than what our grandmothers and great-grandmothers had. It is no longer socially acceptable to joke on TV about beating your wife or to grab your secretary’s rear end.

Today, obstetric violence is one of those fairly normal life experiences that hasn’t aged out yet. Every young person on a college campus has heard “No means no” in the context of sexual consent. But when that same person is giving birth in a contemporary medical setting, we remain firmly in an era where “No means just get it over with faster” and “If she didn’t want it, she wouldn’t be here.” It reminds me of what a doula shared about a birth in 2022:

Finally, my client yelled at Dr. G to stop touching her without her consent and Dr. G responded by saying something along the lines of “This is why you are here. You are giving birth in a hospital because you wanted a doctor. If this isn’t what you wanted, why are you here?”

I hear a doctor saying that your consent rights are the trade-off you make to receive medical care in birth. That is the jist of it, the normalization of the violence. That maternity care means the appropriation of your body and erasure of your humanity. It breaks my heart that so many people believe this without critical thought, and can’t conceive of maternity care that is not violating.

Birth may be traumatizing, but maternity care doesn’t have to be. Models like community-based midwifery and the emerging concept of Trauma-Informed Care center the birthing person, their rights, and their choices as a whole person. We don’t have to continue perpetuating rape culture in birth; we can choose something different.

Whatever the model and whatever the setting, we must be clear about our affirmative responses to the questions, “Do our bodies still belong to us on the day we give birth? Does our consent matter?” We must stand behind birthing people when they say they have been traumatized and abused and when they assert: My consent matters–in all settings. I own my body–at all times.