I remember my very first international conference on human rights in childbirth–Belgium in 2014. As one of the few U.S. attendees, I had expected to be an outsider learning about things foreign to me. Instead, I was struck by the consistency of the themes throughout Europe (for that conference) with what I knew of the U.S. as far as obstetric violence and persecution of out-of-hospital (or community) birth. Even among very different cultures, resource levels, and health systems, the patterns were remarkably similar when it came to the language used against birthing people, the punitive/paternalistic attitudes towards them, and the nature of the human rights violations they suffered.

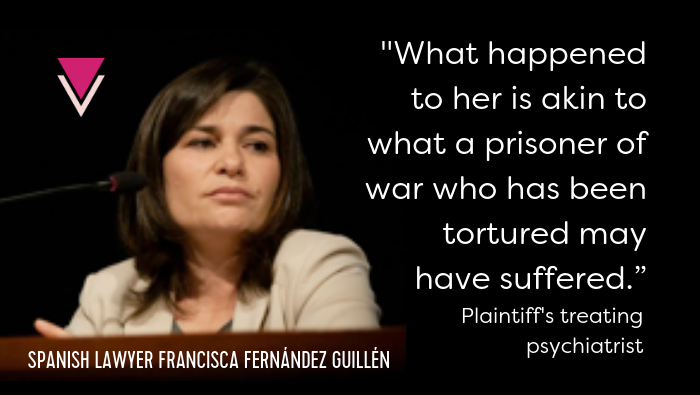

Francisca Fernández Guillén is a Spanish colleague I had the pleasure of meeting at one of those conferences several years ago. She is a feminist lawyer who specialises in sexual and reproductive health and patient’s rights and who collaborated as an expert with the Women’s Health Observatory (part of Spain’s Ministry of Health) on the development of the “Strategy for Assistance at Normal Childbirth in the National Health System.” She also gives training and talks for professionals on health legislation and bioethics and contributes articles and opinion pieces to journals and specialist press (her website).

Coordinated by Francisca, a team of Spanish lawyers have recently filed four claims against Spain with the European Court of Human Rights related to the violations of these women’s human rights in childbirth. Below are summaries of those cases, graciously provided for us in English by Francisca and her team. (Readers who have taken Birth Monopoly’s Know Your Rights: Legal and Human Rights in Childbirth for Birth Professionals and Advocates course will recognize the references below to the European Court of Human Rights’ articulation of the “fundamental human right to choose the circumstances in which [we] give birth” from the 2010 decision in Ternovszky vs. Hungary.)

Sadly, whether you are reading this from the U.S., Argentina, or Ireland, I think you may find these stories sound very familiar: medical procedures and surgery without consent, disrespectful and demeaning treatment resulting in PTSD, and systemic dismissal of these women’s rights to informed consent, bodily integrity, and autonomy.

NOTE: Just this week, Francisca and Roses Revolution founder Jesusa Ricoy Olariaga reported that a judge ordered the arrest of woman in Oviedo (Asturias, Spain), who was then taken to the hospital against her will for an induction of labor on April 24. The woman, 42 weeks pregnant with a healthy, normal pregnancy, had been planning a home birth and was being monitored by her midwife. It appears that she voluntarily went to the hospital for additional testing, where they recommended she have an induction. She and her husband were still deciding what to do when the hospital intervened to initiate the chain of events that led to her arrest and forced induction. After about two days of the induction, she was taken to surgery for “failure” to progress. Imagine the stress of giving birth under those circumstances–taken into physical custody while heavily pregnant, your body literally forced to contract and dilate, under the supervision of strangers who view you as some sort of baby-containing object. Updates from Jesusa are here. A petition about this situation is here.

Case #1: Summary of Complaint of Mrs. J.S.A.

“[T]he conduct of the woman at every moment has NOT been AT ALL collaborative.”

– Treating midwife

On November 3rd, 2012, after a normal and well-managed pregnancy, Mrs. S. arrived at Hospital de Cruces (Vizcaya, Spain) to give birth. From the moment that she entered the delivery room, the midwife adopted an authoritarian attitude: she forced her to stay face-up without moving, didn’t allow her to drink and restricted the presence of the future father.

The labor proceeded normally, however, when the baby was just about to emerge the midwife wanted to perform an episiotomy (cutting of the skin, muscles, nerves and fasciae that surround the vagina). The firm and repeated opposition of Mrs. S. did not stop the midwife taking advantage of her defenseless position in order to make the cut anyway. In the clinical history, the midwife wrote:

“In summary the conduct of the woman at every moment has NOT been AT ALL collaborative. Opposing any postural indications, episiotomy, cutting of the cord, placing her hands on her perineum… and impeding any and all maneuvers/handling [maniobra]. VERY DIFFICULT the whole time.”

Once her daughter was born, the midwife prevented skin to skin contact with the mother, and when the nurses aids went to congratulate Mrs. S. on the birth, the midwife told them not to do so because “she’s behaved very badly” and “she doesn’t deserve this baby.” She told Mrs. S. that she would put it in her medical history and that “I’d have to take the baby from you because you’ve behaved so badly.” “If you had gone to Quirón (private hospital), you would have had a C-section, you’re lucky that you got me.”

Hearing these comments, Mrs. S. felt humiliated and ashamed and was not able to even demand that they she be given her newborn daughter. During the following weeks and months she felt very emotionally fragile. She constantly relived the birthing experience and had nightmares at night. She was not able to share her experience with the people closest to her, she felt uncomfortable in the presence of pregnant women and woke up distraught, vividly reliving the birth. She tended to cry daily, felt guilty for what had happened and questioned what she could have done to avoid the mistreatment. The experience produced intense anguish and a feeling of loss of control at not being able to avoid the flashbacks, and she eventually came to think that it would have been better to not have had her daughter so she wouldn’t have to suffer this way.

At a physical level, the episiotomy caused stress incontinence and pain. The repercussions in her married and sexual life have been severe, resulting in avoidance of sexual relations, insecurity about her body image, and dysmorphia with respect to her genital zone. She feels worthless and ugly when seeing that there is a large hole left in the vulva. She cries during sexual relations, which have been unsatisfactory, despite the affection and love that she feels towards her husband. All of this has entailed a grave loss of self-esteem and confidence in herself. Her relationship with health professionals is also affected, as she has lost confidence in them.

In October 2013, she filed a complaint before the criminal courts that was closed without any investigation. Although the Appeal Court ordered the Court to investigate what had transpired, the court once again closed the case. During the judicial process, gynecological and obstetric expert reports were submitted that detailed that there was no medical necessity to perform the episiotomy on Mrs. S. An expert psychiatric report was also attached that provided evidence for the psychological scars and a diagnosis of Post-Traumatic Stress in relation with the mistreatment suffered during birth. However, all of the evidentiary material submitted by the victim was ignored.

After having exhausted all domestic remedies within our national jurisdiction to obtain the protection of Mrs. F’s rights, reaching the final instance (Constitutional Court), we consider that the judicial decisions have forsaken the rights to dignity, liberty, physical and moral integrity and equality, thereby violating the Spanish Constitution, the international human rights conventions ratified by Spain, with special reference to the Convention for the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women, the recommendations of this Committee, the declarations of the WHO in relation to the prevention and eradication of lack of respect and mistreatment during childbirth care in health centers, and the jurisprudence of the European Court of Human Rights. According to the latter, the right to take decisions about ones’ own maternity form part of the respect for private and family life, with the right of women to decide autonomously during pregnancy, labor and postpartum period being an area of application of Article 8 of the ECHR.

The Spanish State has also failed in its obligation to adopt the necessary measures to modify or abolish the prevailing customs and practices that discriminate against women. In this sense, allowing discriminatory attitudes, such as mistreatment during birth and other forms of obstetric violence based on gender stereotypes such as privileging the reproductive function of the woman, her infantilization or the perception that she is incapable of making decisions over her health and her own body, is proof of the State’s total neglect of demands for protection made by victims of violence in the health sector, negligence for which there have as yet been no consequences.

Case #2: Summary of the Complaint of Mrs. S.F.M.

“It is the doctor who decides whether or not to perform the episiotomy.”- Trial judge

On September 26th, 2009, during a normal and well-managed pregnancy, Mrs. F. arrived at the Xeral Calde Hospital in Lugo, part of the Galician Health Service, as a precautionary measure and in order to receive some guidance as she was experiencing prodromal contractions. She was admitted too early in the labor and 9 vaginal exams were conducted on her, causing her to contract an infection with intrapartum fever, necessitating that antibiotics be administered and her daughter be admitted to the neonatal unit upon birth.

She was given oxytocin (a medicine not without risk which is used to stimulate labor) without a medical indication for this use and without obtaining her consent. The future father’s presence was restricted, and she was forced to give birth lying on her back and with her legs in stirrups. The attendants directed her pushing, contrary to what is recommended by current scientific literature, and finally extracted baby M. using instruments and by performing an episiotomy (cutting of the skin, muscles, nerves and fasciae that surround the vagina).

No one informed Mrs. F. of the medical indication for these techniques, the indications which made them necessary, existing options or alternatives, nor the risks and benefits of these procedures; information which she would have needed in order to give informed consent. She was, in summary, totally ignored as a rational subject, as a person capable of reasoning and understanding and taking appropriate decisions about her own health and that of her daughter. Furthermore, the placenta was manually extracted, against what is medically indicated in this case.

They only allowed her to see her daughter for 10-15 minutes every three hours and the father was only allowed to see his child twice a day for 30 minutes. They bottle-fed the child without her permission, despite the fact that the mother had indicated that she wished to breastfeed. This subsqeuently made breastfeeding and bonding very difficult.

As a result of the above, Mrs. F. suffered physical damage consisting of hypotonia of the pelvic floor, with contracture of the scar from the episiotomy, recovery from which requires specialized physical for pelvic floor rehabilitation. Furthermore, she suffered vaginismus and Postpartum Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD). Dysparuenia due to the scar contracture from the episiotomy, and the vaginismus lasted for 1 year and nine months.

She also suffered moral injury from being deprived of her right to make informed decisions about her own health and her own body, and represent her daughter in taking decisions relating to her child’s health alongside the father. She also suffered pecuniary/financial loss relating to the costs incurred in the resulting consultations and treatments.

When the complaint was presented before the Administrative Courts, the court of first instance/trial judge omitted any reference to the violation of Mrs. F’s right to informed consent, merely stating that “it is the doctor who decides whether or not to perform the episiotomy.” The appellate court declared that requesting consent for the episiotomy was “implausible” and that it was a “technical decision.” Mrs F. provided reports from experts demonstrating that the interventions were contrary to what is considered good obstetric practice. These reports were not taken into account.

After having exhausted all domestic remedies within our national jurisdiction to obtain the protection of Mrs. F’s rights, and reaching the final instance (Constitutional Court), we consider that the judicial decisions have forsaken the rights to dignity, liberty, physical and moral integrity and equality, thereby violating the principles enshrined in our Spanish Constitution, the international human rights conventions ratified by Spain, with special reference to the Convention for the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women, the recommendations of this Committee, the declarations of the WHO in relation to the prevention and eradication of lack of respect and mistreatment during childbirth care in health centers, and the jurisprudence of the European Court of Human Rights. According to the latter, the right to make decisions about one’s own maternity forms part of respect for private and family life, with the right of women to decide autonomously during pregnancy, labor and postpartum period being an area of application of Article 8 of the ECHR. Women have the fundamental human right to choose the circumstances in which they give birth: the ECHR is the first court that articulates this right in these terms, based on a respect for the rights to privacy, autonomy and control of the woman giving birth over her own body.

The Spanish State has also failed in its obligation to adopt the necessary measures to modify or abolish the prevailing customs and practices that discriminate against women. In this sense, allowing discriminatory attitudes, such as mistreatment during birth and other forms of obstetric violence based on gender stereotypes such as privileging the reproductive function of the woman, her infantilization or the perception that she is incapable of making decisions over her health and her own body, is proof of the State’s total neglect of demands for protection made by victims of violence in the health sector, negligence for which there have as yet been no consequences.

Case #3: Summary of the Complaint of Mrs. M.D.C.

“What happened to her is akin to what a prisoner of war who has been tortured may have suffered.” – Treating psychiatrist

On January 6th, 2009, Mrs. M.D., pregnant with her first child and after a normal and well-managed pregnancy, arrived with contractions at the Virgen del Rocío hospital in Seville, where they performed a major abdominal surgery (C-section) on her, because the labor and delivery room was full. The treatment she received has left her with grave physical and psychological scars.

From the first instant, the Hospital personnel intervened in a birth and pregnancy that presented as absolutely normal, subjecting it to what is known as a “cascade of interventions.” Despite not presenting with the symptoms which conformed to the circumstances indicated by scientific literature for admitting laboring women to the hospital, Mrs. C was admitted immediately upon arrival. They artificially ruptured the amniotic sack and administered oxytocin, from which point her contraction pattern changed. They did not ask her consent for any of these three procedures (admission, rupture and administration of oxytocin). The risks were not explained to her nor were alternatives offered, despite the fact that alternatives are advised since none of the interventions are without risk.

At the same time that these procedures were performed without medical indication, they denied her a treatment that she had been prescribed, which was the administration of antacids for her hiatal hernia, a condition that causes stomach acids to come up through the throat, producing a painful burning sensation. The midwife forced her to lie on the hospital bed face up, with legs open and flexed slightly without moving. The lithotomy position is wholely counterproductive when a person suffers from her condition.

To administer epidural anesthesia she was punctured up to 10 times in the back, 9 of which failed, by medical students or residents — non-experts. The catheter had to be reinserted into the spinal column repeatedly; a process that normally takes no more than 10 minutes was prolonged over 1 hour. As a consequence of these punctures she was left with a lesion called “bilateral osteotendinous hyporeflexia in the lower limbs and claudication in a standing position in heels and toes of probable radicular medullary origin.”

Finally, according to what a nurse told her, when they were about to take her to the delivery room to give birth they decided to take her instead to the operating room, due to what appears to be an overcroding of the delivery room. In response to Mrs. C’s refusal, they informed her husband that she would be operated on and, disregarding her pleas, took her on the stretcher to the operating room, while the baby’s head was already in the vaginal canal.

The fetal monitoring graphs show that the baby was stable throughout all of this. After the C-section, they denied her medication for postoperative pain, despite the cries of the patient. This is not medically justified because postoperative pain medication after C-sections is given per protocol.

With respect to the damage suffered as a consequence of these interventions, she is left with a neuropathic lesion, generalized weakness, anemia, insomnia and anxiety. She cannot care for her daughter and is totally dependent on others to manage her daily life. She had to move from Seville to Badajoz, to the home of her parents, due to her limited autonomy. She was diagnosed with Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) that had to be treated intensively with anti-depressant medication. According to the psychiatrist that treated her: “what happened to her is akin to what a prisoner of war who has been tortured may have suffered.”

Over more than two and a half years she had to undergo a multitude of diagnostic tests and pursue neurological treatment, rehabilitation and psychotherapy, with intensive medication.

When a Claim for of the public service was presented, the Andalusian Service did not resolve the case, forcing Mrs. C. to initiate an arduous judicial procedure. Over the course of this process, the judges have omitted the guarantees that, in respect to informed consent, are required by Spanish law and jurisprudence, ignoring the opposition of Mrs. C. to the C-section as well as the omission of the treatments that she required, and taking for granted the information given to the husband as “informed consent” for the C-section.

After having exhausted all domestic remedies of our national jurisdiction, including taking the case to the European Court of Human Rights, we consider that the judicial decisions have forsaken the rights to dignity, liberty, physical and moral integrity, thereby violating the principles enshrined in our Spanish Constitution, the international human rights conventions ratified by Spain, with special reference to the Convention for the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women, the recommendations of this Committee, the declarations of the WHO in relation to the prevention and eradication of lack of respect and mistreatment during childbirth care in health centers, and the jurisprudence of the European Court of Human Rights. According to the latter, the right to take decisions about one’s own maternity form part of the respect for private and family life, with the right of women to decide autonomously during pregnancy, labor and postpartum period being an area of application of Article 8 of the ECHR. Women have the fundamental human right to choose the circumstances in which their birth takes place: the ECHR is the first court that articulates this right in these terms, based on a respect for the rights to privacy, autonomy and control of the woman giving birth over her own body.

The Spanish State has also failed in its obligation to adopt the necessary measures to modify or abolish the prevailing customs and practices that discriminate against women. In this sense, allowing discriminatory attitudes, such as mistreatment during birth and other forms of obstetric violence based on gender stereotypes such as privileging the reproductive function of the woman, her infantilization or the perception that she is incapable of making decisions over her health and her own body, is proof of the State’s total neglect of demands for protection made by victims of violence in the health sector, negligence for which there have as yet been no consequences.

Case #4: Summary of the Complaint of N.A.E.

“They put me on the operating table as if I was a doll. No one tried to calm me. I cried a lot.”

– N.A.E. (mother and plaintiff)

During a normal and well-managed pregnancy, Mrs. N.A.E., who at the time was 25 years old, arrived at the Donostia public hospital, part of the Basque Health Service, as her waters had broken. There, they induced her labor prematurely and she ended up having an unnecessary C-section. During the process, the health personnel infantilized her and deprived her of the right to make informed decisions. Her physical and psychological priorities and needs were ignored. The surgeons used the operating room like a classroom, using her as an example for students to learn techniques for performing a C-section.

“They put me on the operating table as if I was a doll. No one introduced themselves, no one talked to me, no one looked me in the face. No one tried to calm me. I cried a lot. They crossed my arms. The operating room was full of people, it seemed like a public plaza, they ignored me and shouted among themselves, “Where is the baby’s heartbeat?” I was there alone and naked and people came and went, the door kept opening and closing. They talked among themselves about their things, all very important and indispensable in an operating room: what they did on the weekend, that this or that person is sick… They talked, without it mattering that I was there and that my son was about to be born, that he would only be born once, they didn’t let me experience it. A doctor that was acting in the role of a teacher was guiding the steps (information that I would rather not have had to hear) for the people who were operating on me, he was telling them how they should cut and what they were cutting and moving… The anesthesiologist is the only person that at any time paid attention to me and tried to calm me. I was shaken up. Someone was explaining what they have to do. I couldn’t believe it, I asked that there be no more people and there were so many voices! They didn’t stop speaking for a second, not even when my son was born.”

Once born, the baby was separated from his mother. He was shown to his mother at the height of her hand, but she could not touch him because they had restrained her arms in a crossed position for the operation and left her like this. They ordered her to give him a kiss, bringing him close to her face, but before she could even speak they took him away. She instead had to listen to how the teacher explained to the students how to sew her up. Her cries for them to bring her baby during the hours following the operation were ignored. They neither informed her husband that she had left the operating room nor was he allowed to accompany her during the following hours.

During the postpartum period, Mrs. N.A.E. went to her primary care physician for symptoms of anxiety in relation to the experience with the birth. In a report from 7/6/2013, the psychiatrist at the Andoian Mental Health Center (Basque Health Service), Dr. Z. diagnosed her with Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) and prescribed anti-anxiety treatment. Dr. Z. describes:

“The patient’s clinical presentation is compatible with Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (F43.1) following a difficult and stressful situation experienced 11 months prior. The woman recounted the experience in the hospital where she gave birth to her son by C-section.

From that day, and secondary to the treatment the patient was referred to by the hospital services, began symptoms of anticipatory anxiety that has led her to delay personal medical check-ups, in addition to an exaggerated fear of hospitals, symptoms which the patient had not previously experienced […] We observed clinical anguish and anticipatory anxiety, emotional and depressive-reactive mood that was impacting her daily life.”

She presented a Claim for before the health service which was accompanied by an expert obstetric report that reveals harmful practices in the care she was given and puts in sharp relief the fact that there are existing alternative therapeutic methods which were not practiced and that could have been used to avoid a C-section. Similarly, the expert psychiatric report reveals that the feeling of impotence which always accompanies presentation of PTSD could have been avoided through informed consent, because it allows the person to have control over their life, accepting or rejecting the interventions and preparing themselves to assume possible adverse results. The violation of personal and family privacy is also revealed in the report as a traumatic factor.

Therefore, as a consequence of the manner in which the Public Health Service acted, Mrs. N.A.E. was subjected to a major abdominal surgery (C-section) along with its potential risks which means her future pregnancies pose a higher risk, and additionally she now suffers from PTSD.

During the judicial proceedings that followed, the psychiatrist from the health center that diagnosed Mrs. N.A.E.’s condition was pressured to change the diagnosis. The judge did not allow the experts to give testimony in court, nor did the judge take into account their written reports. The Constitutional Court did not admit the application for amparo.

After having exhausted all of the domestic remedies of our national jurisdiction, we consider that the judicial decisions have forsaken the rights to dignity, liberty, physical and moral integrity and equality of Mrs. N.A.E., violating the Spanish Constitution, the international human rights conventions ratified by Spain, with special reference to the Convention for the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women, the recommendations of this Committee, the declarations of the WHO in relation to the prevention and eradication of lack of respect and mistreatment during childbirth care in health centers, and the jurisprudence of the European Court of Human Rights. According to the latter, the right to take decisions about one’s own maternity form part of the respect for private and family life, with the right of women to decide autonomously during pregnancy, labor and postpartum period being an area of application of Article 8 of the ECHR.

The Spanish State has also failed in its obligation to adopt the necessary measures to modify or abolish the prevailing customs and practices that discriminate against women. In this sense, allowing discriminatory attitudes, such as mistreatment during birth and other forms of obstetric violence based on gender stereotypes such as privileging the reproductive function of the woman, her infantilization or the perception that she is incapable of making decisions over her health and her own body, is proof of the State’s total neglect of demands for protection made by victims of violence in the health sector, negligence for which there have as yet been no consequences.