When we educate clients and providers about informed consent in maternity care, we usually talk about it in sort of a transactional way: the medical professional is obligated to share certain information, and the patient then selects from among the choices based on the information provided. It’s a formula: here’s your info on risks, benefits, and alternatives; thank you, here’s my choice.

But this narrow view of informed consent as a simple information exchange misses a whole lot: most of all, the power dynamics that are built into the setting where it occurs. As it turns out, power is a major part of the discussion around consent in general.

A Culture of Non-Consent

It’s hard to talk about informed consent in birth when our cultural understanding of “consent” in general is so skewed. Our national definition of consent is still very broad; everyone agrees that “yes” is consent, but many people also believe (and law, unfortunately, sometimes supports) that consent can also mean the absence of no, a capitulation to pressure, or a moment in time where we said yes and then felt obligated to stick with that yes even when circumstances or our minds changed–also known as “implied consent.”

I cringe when I re-watch the “classic” movies I grew up with, where this loose understanding of consent in sex is reflected and reinforced. Look at most any movie made in the 20th century (and into the 21st), where the men chase and the women are chased. The men persist until the women give in, and then everything is rosy. Remember that famous scene from Gone With the Wind where an irate Rhett Butler grabs Scarlett’s head and threatens to crush her skull, and then drags her upstairs to the bedroom against her will? The next scene is her sitting up in bed in the morning with sparkling eyes and smile. Look at Grease: they sing, “Did she put up a fight?” Look at Sixteen Candles, where a boy literally passes his blacked-out drunk girlfriend on to another guy.

We are immersed in scenes like these all our lives, and the beliefs they represent run deep in our psyches. It’s no wonder our idea of “consent” is so shapeless when it comes to another aspect of our reproductive lives: pregnancy and childbirth. If our consent boundaries have been porous all our lives, it’s not too hard to be pushed into something involving our most intimate parts and still consider that “consent.” Worse, when we do “give in” to someone pushing on our boundaries, we often still blame ourselves for whatever happens. We say, “Well, I did let him do it.” We take the fall and let “him” off the hook. “He” was doing what he does, and we didn’t fight back hard enough.

All of this applies to birth. We hear stories daily of manipulation, coercion, force, and procedures being casually introduced as if the patient has no choice. “Implied consent” is often invoked inappropriately to make people think they’ve given up their consent rights once they are admitted to the hospital–that they are not allowed to say “no” or to change their minds once they’ve said “yes.” My podcast is full of examples of all these things.

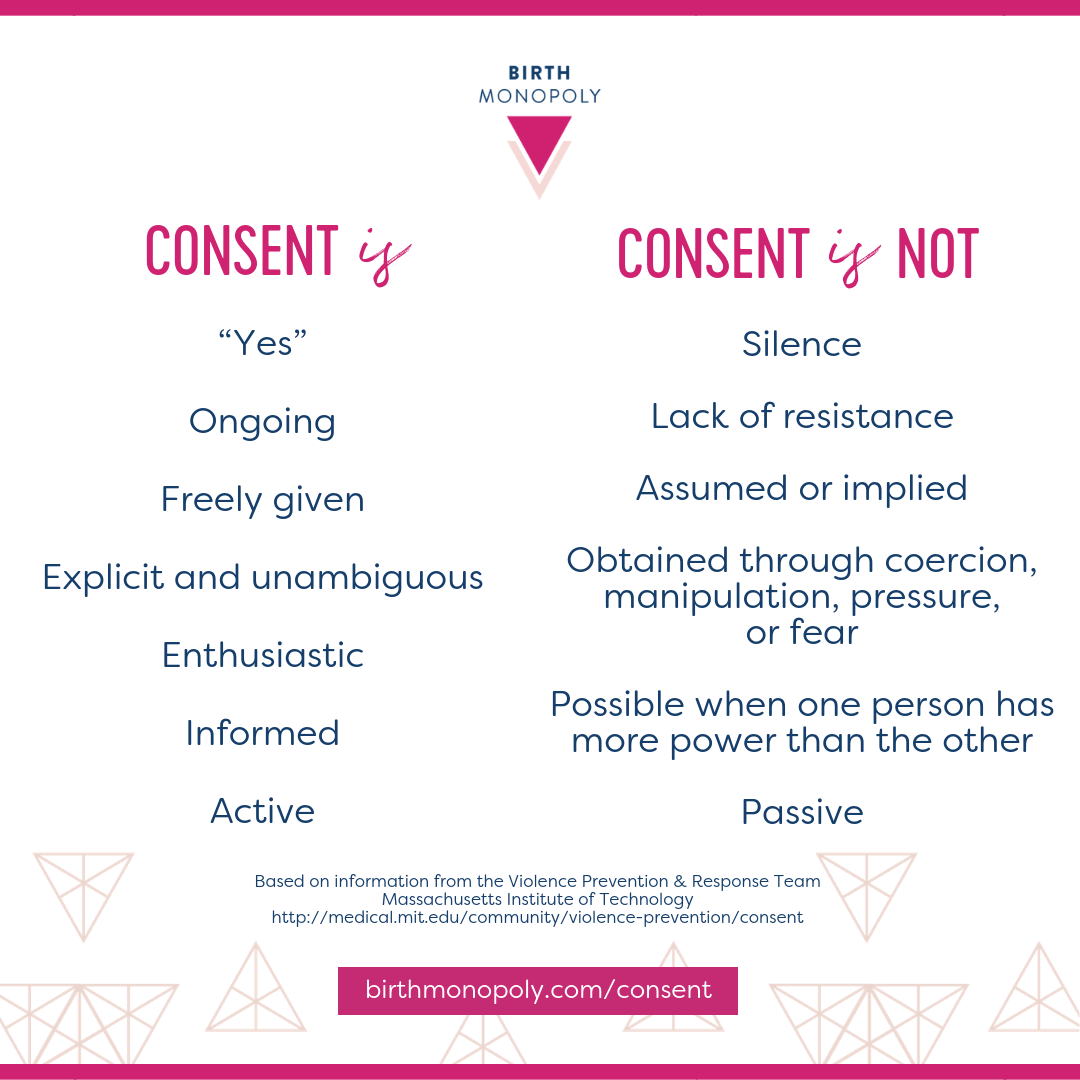

So, to move the conversation toward a more robust understanding of consent, I created this image using information adapted slightly from the rape education materials from the Violence Prevention & Response team at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Consent and Power

How interesting is the item above about when one person has more power? I decided to leave it in the list word-for-word from the MIT team because we need to talk openly about how the express hierarchy of power in maternity care complicates consent conversations. I certainly would not say laboring people are inherently unable to give consent because they have less power than medical professionals–but I would say that we can’t talk about consent in the context of maternity care without acknowledging the real power dynamics at play.

In sex, we recognize that certain power dynamics, like those between a child and an adult or a professor and a student, make consent impossible. Likewise, we must recognize that powerful dynamics are also at play in the birth room–an extreme differential between someone with professional privilege and implied authority, on their home turf, interacting with a patient in pain, on their back, in an unfamiliar environment, often with little support. Even more powerful are the years of cultural conditioning around mothers as martyr-vessels and medical professionals as authorities to be obeyed. This dynamic has at least as much to do with what happens in the birth room as the patient’s preferences do.

If you are a medical professional reading this, imagine how it would feel if you were required to talk to patients while sitting cross-legged on the floor of the room while looking up at them, wearing a toga that didn’t quite cover your knees, while nurses felt comfortable stepping over you and interrupting your conversation as you tried to do your job from the floor. I imagine most physicians would balk at this idea, because we can all feel how undignified it is. Your literal and figurative position is lowered, and that affects how you interact with others.

To take it even further with the power dynamic, now pretend your medical training is seen by the world as a liability rather than an asset. “Well, he’s a doctor,” someone might say. “Everyone knows they are too tired and traumatized to be rational.”

These power dynamics are especially potent because there are 1) sometimes huge consequences for patients whose consent is violated, in the form of trauma, PTSD, physical injury or complications, and loss of trust in the medical system, and 2) almost no consequences for medical professionals who violate consent. Although the stakes are very high for patients, there are no checks and balances for this power dynamic; if anything, it is systemically enforced.

How do we change this?

I’d love to hear your thoughts in the comment section. And as we talk about strategies and tactics that individuals can employ, I want to be clear that we can’t fix this power differential on our own. It requires a systemic, top-down realignment of who is considered the legal authority in the room. But that’s a conversation for another day (doulas, start with the basics in my Know Your Rights course!).

I will share what has been most helpful for me on a personal level: building up my consent boundary muscles. It means knowing in my bones what consent feels like so that when someone is pushing on my boundary, I notice instantly. Working at that and exercising those muscles mean my red flags get stronger, faster, and more accurate over time. I recognize it right away when a boundary is being challenged, and then I get to decide what to do about it.

This is a work in progress for me, and pushing back is a whole other set of muscles around how we handle confrontation. But before that, you can practice holding firm, knowing that your boundary keeps you safe and you don’t have to explain or justify your boundary. Just that it is there, and you trust it.

So, my suggestion for doulas is to help your clients strengthen those consent boundary muscles while being realistic that you can’t undo decades of conditioning. This is a delicate place where we have to be clear about where the doula’s responsibility ends and where the client’s begins.

Teaching about informed consent in relation to specific procedures is a natural place to shift the conversation on consent as being rooted in “yes” rather than an absence of no or a capitulation to pressure. Prenatally, you can emphasize consent throughout by asking permission at every step (“Is it okay if I touch you?”); tuning in carefully to your client’s cues including tone of voice, facial expression, and body language; and reflecting back when you pick up that consent is not enthusiastic and unequivocal. (“You know, I heard you say yes, but you look uncomfortable. If you don’t want to practice labor positions right now, I don’t want you to agree just because I suggested it. You’re always the boss, remember? What do you really want to do right now?”)

And yes, you can help shift the power dynamics in the hospital by modeling healthy boundaries, by being a source of power yourself. In fact, not doing those things creates a void for your client, who invited you there to stand by their side in solidarity. Doulas are not martyr-vessels, either. Healthy, strong boundaries go hand in hand with respect and love.

I wish doulas could ask these questions in the birth room:

“Do you feel like you’ve got enough information right now to make a decision you feel good about?”

“If no one else were in the room and you could do anything right now, would this be your choice?”

“If you were to look back on this moment, would you say, ‘I wish I had held out longer’? What does that mean?”

“Are you okay with what’s happening right now? Are you still saying, ‘Yes’ to this?”

In the bedroom or the birth room, true consent is not just an absence of no, and it is never implied nor coerced. Let’s work on reframing consent in birth into what it should be in all aspects of our lives: an active and ongoing choice where the power to say “yes” or “no” lies within each of us.

Cristen Pascucci is founder of Birth Monopoly. A former public affairs professional, she served as vice president of Improving Birth from 2012 to 2016, spearheading media and consumer campaigns on the maternity care crisis and obstetric violence, and running a legal advocacy hotline with birth lawyers. Today Cristen teaches Know Your Rights: Legal and Human Rights in Childbirth for Birth Professionals and Advocates, hosts Birth Allowed Radio, and is making a documentary film called Mother May I on obstetric violence and birth trauma.

Cristen Pascucci is founder of Birth Monopoly. A former public affairs professional, she served as vice president of Improving Birth from 2012 to 2016, spearheading media and consumer campaigns on the maternity care crisis and obstetric violence, and running a legal advocacy hotline with birth lawyers. Today Cristen teaches Know Your Rights: Legal and Human Rights in Childbirth for Birth Professionals and Advocates, hosts Birth Allowed Radio, and is making a documentary film called Mother May I on obstetric violence and birth trauma.